Tag: book

Review of the Arabic version of my book in the Independent Arabia (16 May 2022)

The novelist and journalist Ali Ata published a flattering and very complete review of my latest book in the newspaper… read more Review of the Arabic version of my book in the Independent Arabia (16 May 2022)

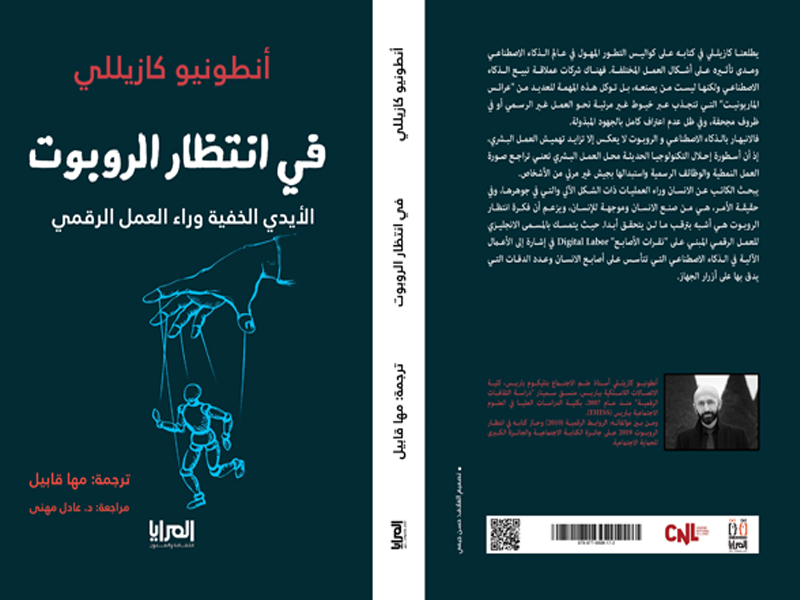

The Arabic translation of my book “Waiting for Robots” has just been published! (2 Feb. 2022)

After the Italian and the Spanish translations of my latest book [Waiting for Robots. An Inquiry Into Digital Labor] En… read more The Arabic translation of my book “Waiting for Robots” has just been published! (2 Feb. 2022)

Why Bolivia matters to the future of digital economies (plus three talks and one new book!)

It’s been a few months in the making, and now it’s happening: I’ll be in Bolivia to deliver a few… read more Why Bolivia matters to the future of digital economies (plus three talks and one new book!)

New York to San Francisco: my U.S. conference tour (October 20-29, 2015)

If you happen to be in one of these fine US cities, come meet me. I’ll be on a tour… read more New York to San Francisco: my U.S. conference tour (October 20-29, 2015)

Chinese media about “Qu’est-ce que le digital labor ?” (Oct. 3, 2015)

After a press release by Taiwanese agency CNA, several Chinese-speaking media outlets have been discussing the central theses of our… read more Chinese media about “Qu’est-ce que le digital labor ?” (Oct. 3, 2015)

Pourquoi je ne porterai pas plainte contre ceux qui piratent mon livre

“Le jour où l’écrivain découvre que son livre a été piraté et est désormais disponible en téléchargement illégal sur Mediafire,… read more Pourquoi je ne porterai pas plainte contre ceux qui piratent mon livre

One of the greatest comedians of our time: Slavoj Žižek

I’m serious: the marxiste célèbre and #Occupy Wall Street avuncular philosopher Slavoj Žižek is really a funny man. Case in point,… read more One of the greatest comedians of our time: Slavoj Žižek

Larry Lessig's Book on Internet Governance Turns Ten and Goes Creative Commons

Ten years ago, Lawrence Lessig published Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, a groundbreaking study on Internet governance insisting that… read more Larry Lessig's Book on Internet Governance Turns Ten and Goes Creative Commons