Tag: conflict

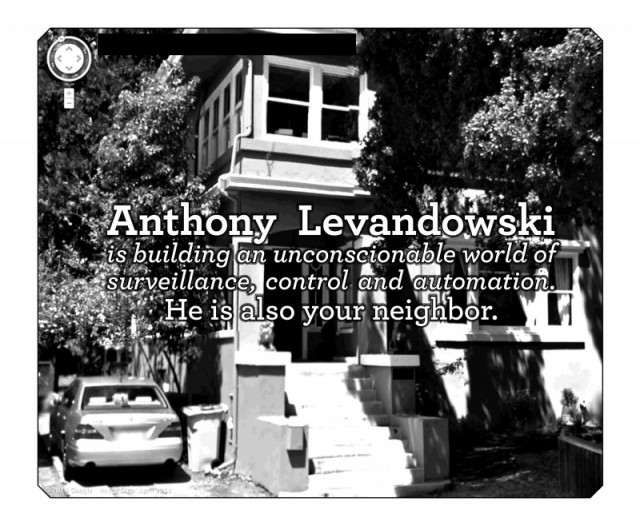

Privacy is not dying, it is being killed. And those who are killing it have names and addresses

Quite often, while discussing the role of web giants in enforcing mass digital surveillance (and while insisting that there is… read more Privacy is not dying, it is being killed. And those who are killing it have names and addresses

admin 23 January 2014

Trollarchy in the UK: the British Defamation Bill and the delusion of the public sphere

[UPDATE 26.06.2102: A French version of this post is now available on the news website OWNI. As usual, thanks to… read more Trollarchy in the UK: the British Defamation Bill and the delusion of the public sphere

admin 12 June 2012

Posted in Non classé

R.I.P. Sandro Roventi (1947-2010) (Sunday Sociological Song)

Italian sociologist Sandro Roventi left us. Yesterday he was put to rest in the cemetery of Lambrate (Milan). Sandro was… read more R.I.P. Sandro Roventi (1947-2010) (Sunday Sociological Song)

admin 17 October 2010