A new working paper authored by three Stanford researchers, titled “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence”, claims that GenAI has significantly reduced employment opportunities for individuals aged 22-25—the metaphorical “canaries” that die first. These “robust results” are supported by “large-scale evidence”, including data from a large payroll database and a dataset owned by Anthropic, the company behind the chatbot Claude. The paper argues that competing explanations for the observed decline, such as subpar university training during the COVID-19 years, are less reliable. Importantly, the employment drop pertains to tasks “automated” by AI, not those “augmented” by it.

This distinction is significant because it connects to the paper’s first author, Erik Brynjolfsson, an “academic and an innovator”—according to his Wikipedia page. He runs a side business, Workhelix, “an AI Fund portfolio company” that helps businesses by promoting a “task-based approach” to measure AI’s impact. Sounds like the paper’s analytical framework, right?

The authors’s reliance on the Anthropic Economic Index, a database linking conversations with Claude to specific tasks and occupations, raises other concerns. With studies like this one, the primary problem is the task-based approach itself, because JOBS ARE MORE THAN A SUM OF TASKS—a point economists have repeatedly failed to understand over the years. The connection between tasks and occupations is far more nuanced. Prompts enter into Claude do not necessarily correspond to a specific job or profession. One might use a chatbot to edit or translate a text without being a professional copywriter or translator.

Further complicating matters, Anthropic has a vested interest in promoting AI adoption. Back in May 2025, its CEO Dario Amodei publicly predicted that AI would eliminate half of entry-level white-collar jobs and drive unemployment up to 10–20% within five years—a claim consistent with the paper’s findings. While there is no formal link between Brynjolfsson and Anthropic, his public endorsement of the company (see his tweets) and involvement in reviewing its CEO’s blog rantings raise questions about the objectivity of the research.

Look, Brynjolfsson isn’t compromised. He’s just fanboying the very companies whose narrative pays his bills. The paper risks lending academic credibility to the automated-versus-augmented tasks framework that Workhelix markets, blurring the line between independent research and business interests.

In the metaphor of “canaries in the mine”, who are the three authors? They are the people who hold shares in mining companies who, instead of caring about workers’ well-being, insist that everyone needs special safety equipment that they sell on the side…

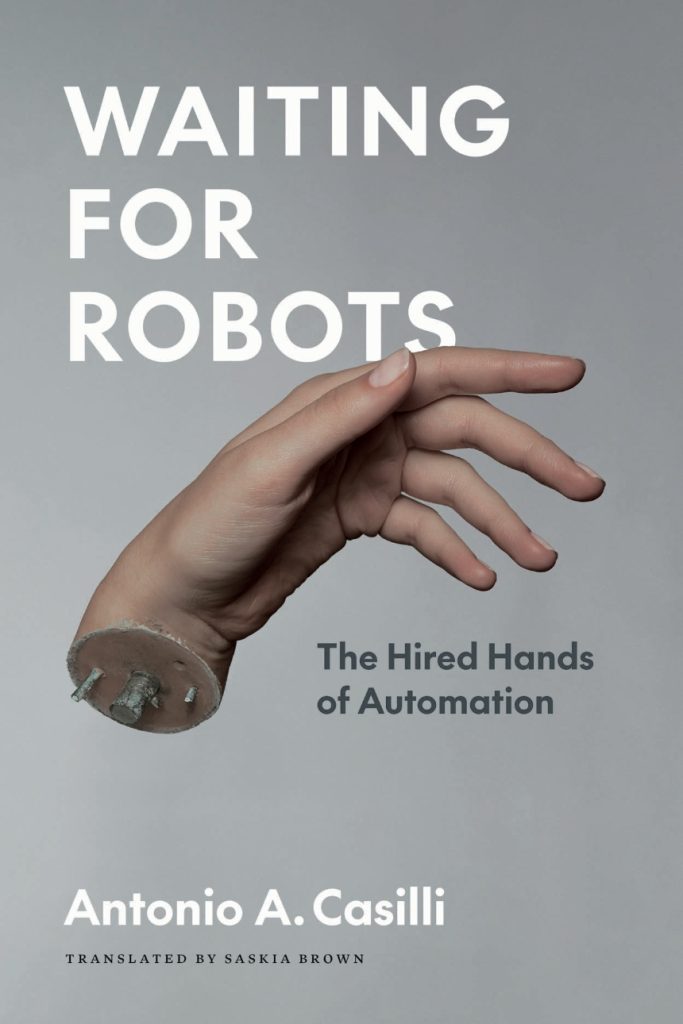

PS. To be clear about my own position on AI-driven job displacement: AI itself doesn’t replace workers. Executives (with the help of shrewd consultants) eliminate positions—rehiring the same individuals as precarious, platform-based contractors—while invoking AI as a convenient justification. I make this point in my book “Waiting for Robots. The Hired Hands of Automation”. You should check it out.

So, what actually explains the employment decline observed in this paper? My hypothesis points to a different culprit: the accelerating shift toward gig work and micro-entrepreneurship that has reshaped labor markets for over a decade. The missing 22-25 year-olds haven’t been replaced by AI—they’ve been reclassified. Instead of appearing in payroll databases as employees, they’re invoicing as independent contractors and platform freelancers. Their labor hasn’t disappeared; it has migrated from payroll records to accounts payable. This represents the culmination of more than a decade of labor platformization, where companies systematically convert employment relationships into vendor relationships, not to accommodate AI, but to shed labor protections and overhead costs.

PPS. Little addendum, courtesy of Christian Gärtner, Professor für HRM & Digitalisierung der Arbeitswelt, Hochschule München (via Linkedin)

“So far, the methodological issues were much more apparent (most of them are stated in the paper but not as harsh as I put them):

– unrepresentative sample: only ADP data which covers mostly service-oriented firms, not the broader (US-)market.

– using (sometimes crude) proxies for what businesses are actually doing: The task analysis is based on ratings from humans and GPT-4 to decide which tasks are automatable and for analysing (a fraction of all) chats with Claude, they assume that job-related questions are an indicator that this job may be automated – plus they cannot know whether the answer was really useful (see https://www.anthropic.com/news/the-anthropic-economic-index)

-The authors use firm-time fixed effects but admit its limits: “One alternative confounder that would not be controlled for with firm-time effects is that even conditional on the firm workers with high Al exposure were excessively hired after the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a subsequent contraction in their hiring” (p. 19). Yes: That might be a plausible explanation, especially considering that the drop in hiring already began in late 2022, well before GenAI could realistically be used to substitute tasks, let alone entire jobs!”