By Antonio A. Casilli & Paola Tubaro. French version provided by OWNI.fr.

This is the first of a series of joint posts of Bodyspacesociety + Paola Tubaro’s Blog. You are kindly invited to visit both websites, featuring plenty of interesting stuff.

Why social media bring democracy to developing countries and anarchy to rich ones?

O sublime hypocrisy of European mainstream media! The same technologies that a few months ago were glorified for single-handedly bringing down dictators during the Arab Spring, are now at the core of an unprecedented moral panic for their alleged role in fuelling UK August 2011 riots. In a recent post, Christian Fuchs rightly maintains:

And, o! exquisite refinement in the ancient art of double standard: the same conservative press that indignantly deplored dictators’ censorship of online communication, now call for plain suppression of entire telecommunication networks – as unashamedly exemplified by this piece in the Daily Mail.

Fact is, moral panic about social media is the specular reflection of the acritical enthusiasm about these very same technologies. They both spring from the same technological determinism that acclaims new gimmicks and buzzwords to smooth away the economic and social roots of unrest.

Having said that, what can we, as social scientists, say about the role of social media in assisting or even encouraging widespread political conflict? Very little indeed, insofar as we do not have data on actual social media use and traffic during riots. It would take months to gather that data – and who can wait for so long in a media environment that spits out “quick and dirty” analyses by the hour?

The best approach is a more innovative one, relying on social simulation. This is a new methodology that compares alternative computer-generated social scenarios to detect what variables come into play in specific social processes1.One of these variables is the use of social media to organize flash-mobs in order to build field-awareness in urban uprising settings. We aim to demonstrate that the more we repress and censor social media in a situation of civil unrest, the worse the situation gets for everybody in a given society.

Epstein’s civil violence model (revisited)

Social scientists have been modelling civil violence via agent-based simulation for almost a decade now2. One major contribution – on which we will build upon for our model – was presented by Josh Epstein in a 2002 article3.

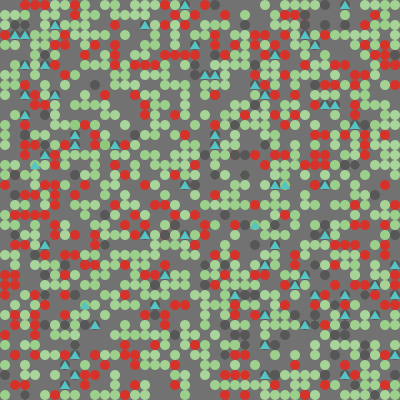

Agent-based simulations are like games based on very simple rules – and bringing forth complex results. The model basically describes a society where there is only one type of social agent (represented by circles in figure 1). (Before you scream at oversimplification, just ask yourself if you feel more comfortable with the political characterization that conservative media have been pushing in the last few days, where there are two types of citizens: “looters” and “those who are ready to defend their communities”. At least, Epstein’s standard social agent reminds us that anyone can become a looter, according to the situation).

The agent’s behaviour is influenced by several variables. The first one is the agent’s personal level of political dissatisfaction (“grievance”, indicated by lighter or darker green colour in figure 1). That can lead this person to abandon his/her expected state of quiet and become an active protester (red coloured circles in figure 1). However, the decision to act out – whether it is to go on a looting spree or to burn the parliament and overturn the government – is conditioned by the agent’s social surroundings (“neighbourhood”). Does s/he detect the presence of police (blue triangles in figure 1) in the surroundings? If the answer to this question is no, s/he will act out. If the answer is yes, another question is asked: is this police presence counterbalanced by a sufficient number of actively protesting citizens? If the answer to this second question is yes, then the agent acts out. Sometimes, in an utterly random way, one citizen gets caught by the police and is sent to jail for a given period of time (black circles in figure 1). (Again, if you are marvelling at the simplicity of this rule, just bear in mind how tricky it is for the UK police to really distinguish who did what in a riot –and how many of these days’ arrests will eventually turn out to be arbitrary).

Figure 1

Circles represent social agents, whose level of grievance is indicated by lighter or darker shades of green. Active protesters are colored red and jailed protesters black. Blue triangles represent police officers.

Of course the model takes into account other mitigating factors, such as the perceived risk of being arrested and government legitimacy. And of course there is the possibility of moving from one place to another to team up with other protesters and run havoc. We will come back to this point because this seems determinant for the use of social media.

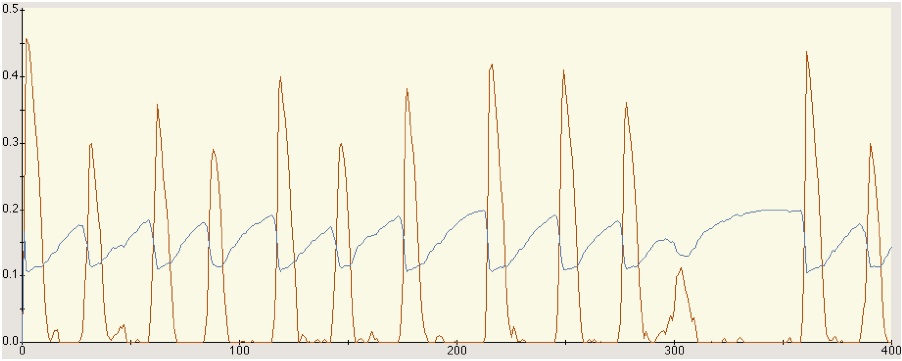

The main result of Epstein’s model is that, in a typical situation, civil violence does not look like a linear process. The naïve vision of political conflict as cumulative processes where confrontation escalates until the government comes tumbling down is fallacious. Civil or political unrest is what Epstein calls a “punctuated equilibrium”. Long periods of stability where rebellion is smouldering are followed by short violent outbursts.

Figure 2

A typical civil unrest pattern: outbursts of violence (red curve) punctuate long periods of stability when political tension is building up (blue curve).

There is another variable which is, to us, crucial for understanding social media use to create flash mobs to deploy in a civil violence situation: this variable is called “vision” in Epstein model. Vision is an individual agent’s ability to scan his/her neighbourhood for signs of cops and/or active protesters. The higher the vision, the wider the agent’s range.

What we have done here is to modify the consequences of “vision”. In the original model4, agents and police officers move to randomly chosen places within their vision range. We have introduced a new rule that makes agents move to places in their vision range that are surrounded by the maximum number of active protesters. The result of the modified simulation (if you wish to download the code, just click here) is consistent with the tactical use of mobile technologies by protesters in order to gain a cognitive advantage against police forces and have a better awareness of the field, its resources and possible weak spots.

This simple change simulates the behaviour of individuals involved in civil unrest, using BBM or Twitter to detect, and to converge in, hot spots. If the value of “vision” is higher (like in a situation where online networking tools are widespread and not censored), each agent has complete information as to what’s going on even in remote locations. If social communication is censored, the value of “vision” is lower, and agents have partial or non-existent awareness of their surroundings and tend to move randomly.

Internet censorship: a source of protracted high-level violence

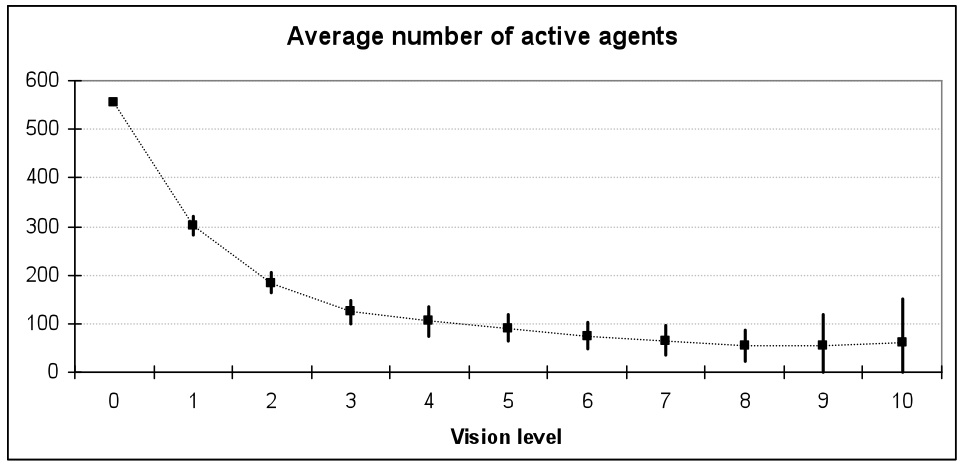

Our social simulation code reproduces the functioning of a certain social system (let’s say a city like London) over a significant period of time (in our case 1000 time steps), for different values of the parameter “vision” caeteris paribus (that is: while leaving the others parameters unchanged – cf. Table 2 in Annex 1 at the end of this post). Running the model again and again and generating alternative scenarios, shows us the outcomes of lower or higher values of “vision” – indicating the effects of more or less censorship of social media.

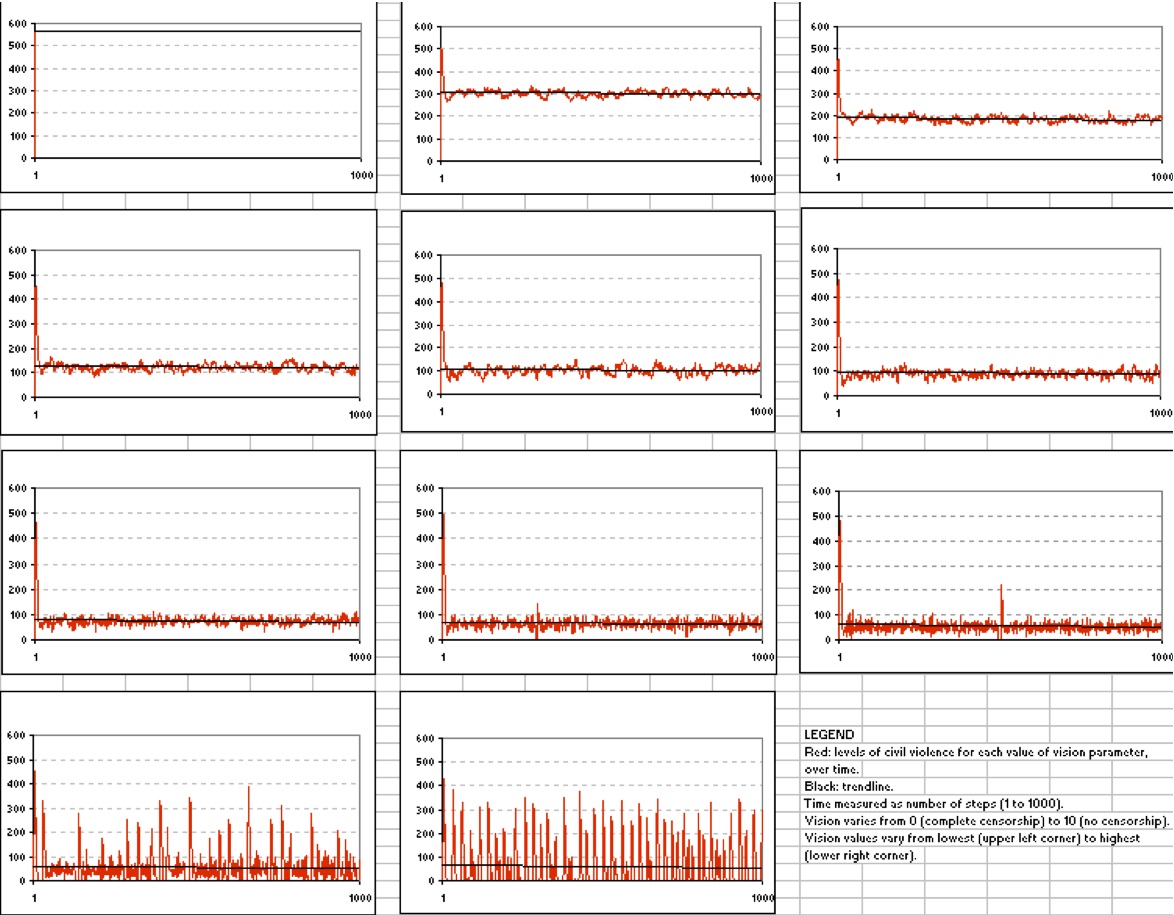

Let’s have a look at the results in figure 3 (click to expand the image):

Figure 3

Figure 3

Red patterns represent number of violent protesters over time within different levels of social media censorship: from 0 vision (total censorship, upper left) to 10 vision (no censorship, lower right).

As we can see, different values of “vision” generate different patterns of civil unrest over time. All scenarios display an initial outburst – pretty much what we have been experiencing in the last few days. What happens next is influenced by the level of censorship government applies. In the case of total censorship (vision = 0) the level of violence stays at its maximum virtually forever. Think Egypt Internet kill switch incident in January 2011 – and remember its consequences on violence escalation in the country and, ultimately, on Mubarak’s regime… The other cases correspond to less and less censorship. Values between 1 (almost complete censorship) and 9 (almost no censorship) correspond to different levels of protracted civil unrest: the stronger the censorship, the higher the average level of endemic violence over time (best linear fit represented by the black lines in figure 3).

The last case, corresponding to perfect social agents’ vision (and thus to no censorship at all) deserves a little more comment. Apparently this situation is characterized by incessant high-level outbursts of violence, with peak active levels that seem to be even more significant that in other cases. Yet, the average trend of violence over time (black fitting line) remains low. Moreover, if we want to measure the size of violent outbursts, looking at their peak active level is not sufficient. Looking at time intervals between outbursts, at the duration of outbursts, and at the level of “social peace” between outbursts, help us discover that this scenario is actually the best for everyone. In the absence of censorship, agents protest, sometimes violently, nevertheless they are able to return to significant levels of quiet (green line in figure 4), when social unrest is halted.

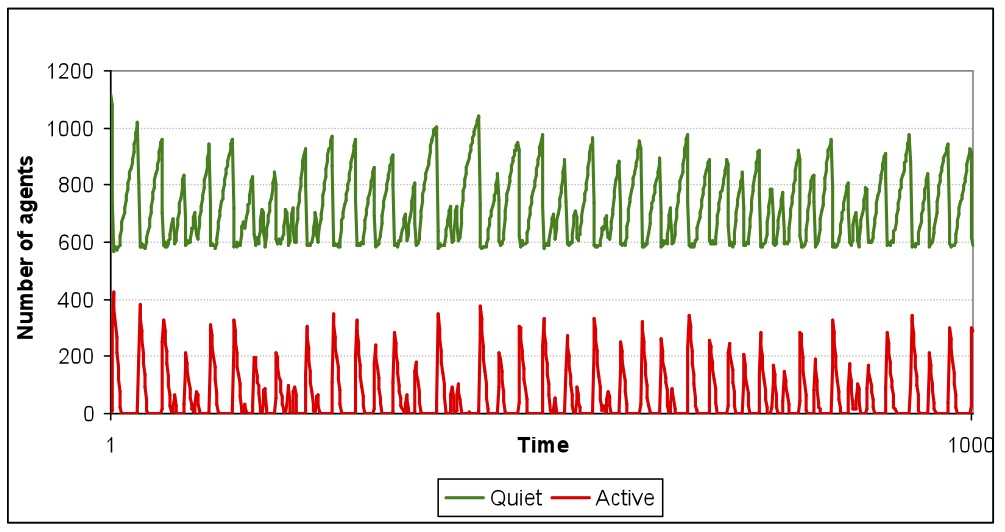

Figure 4

Figure 4

In the absence of censorship, high levels of social unrest are possible (see peaks in red line), but between uprisings social system is able to come back to significant levels of quite (green line)

This is the only scenario where active protest drops down to zero for extended and repeated periods of time (cf. Table 1 in Annex 1 at the end of this post): exactly what Epstein described as “punctuated equilibrium” in his initial model of civil violence. And although that does not seem to match our wildest dreams of social harmony, it still is a situation where citizens are free to voice their dissent on social media, to coordinate their efforts and act about it – albeit in confrontational ways – while still enjoying a higher level of quiet over time (see figure 5).

Figure 5

Figure 5

Levels of civil violence over time as function of levels of censorship. (Higher vision means less censorship and less civil violence).

In the absence of online censorship, social agents have vision= 10. This corresponds to the lowest levels of civil violence over time.

Some concluding remarks

It is not our role to pass judgments on politicians and police officers’ disapproval of “sociological justifications” of the UK riots or on their dismissal of social sciences as – at best – a luxury we can’t afford in times of unrests. Their shoot-first-ask-later stance, although probably moved by good intentions, can lead to ill-advised policy choices, like in the case of Internet censorship that we have chosen to discuss here.

Of course other factors have to be taken into account to use a civil violence model inspired by Epstein. As shown in a recent paper by Klemens et al. (2010) rebellious outbursts are more likely given increased hardship (the recent financial crisis does seem to come into play here). Civil violence is also influenced by loss of government legitimacy – which in this case seems consistent with the unpopular budget cuts promoted by David Cameron, not to mention the recent Murdoch/NoTW phone hacking scandal. Finally, protest outbursts are less likely given increased repressive capacity5. Which does not equate to the naïve argument that “what we need is more cops” – routinely conveyed in situations of civil unrest. Repressive capacity, in the case of UK riots, has been about adapting police procedures to compensate for the clear tactical advantage rioters showed over the first few days of August – an advantage that seemed consistent with the increased level of “vision” and field awareness allowed by mobile communications, as discussed here. The growing presence of MET police and law enforcement initiatives on Facebook, Flickr, and Google groups can actually account for the subsequent limitation of violent outburst by reducing the rioters’ communicational advantage.

Other studies have applied social simulation to censorship in situations of civil violence. Garlick and Chli (2009), for example, insist that restricting social communication pacifies rebellious societies, but has the opposite effect on peaceful ones6. Our intention is to show that the choice of not restricting social communication turns out to be a judicious one in the absence of robust indicators as to the rebelliousness of a given society.

What we have tried to do is to demonstrate how, even in the absence of empirical data, social sciences can still help us interpret how social factors come into play, and possibly avoid trading democratic values and freedom of expression for an illusory sense of security.

To cite this post: Casilli, Antonio A. and Paola Tubaro (2011) Is a social media-fuelled uprising the worst case scenario? Elements for a sociology of UK riots. Joint post Bodyspacesociety/Paola Tubaro’s Blog, August 11, URL:http://www.bodyspacesociety.eu/2011/08/11/is-a-social-media-fuelled-uprising-the-worst-case-scenario-elements-for-a-sociology-of-uk-riots

Annex 1 – Tables

| Vision levels | % time spent in quiet (no civil violence) |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 |

| 8 | 0.3 |

| 9 | 10.2 |

| 10 | 32.5 |

Table 1 – % of time without riots – corresponding to levels of vision.

| Parameter | Values |

| Initial cop density | 4% |

| Initial agent density | 70% |

| Number of cops | 64 |

| Number of agents | 1120 |

| Government legitimacy | 80% |

| Max jail term | 30 time steps |

| Vision | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

Table 2 – Parameters used in the model

- We have presented our approach to this method in this article, in case you wanted to give it a shot. Otherwise just go on reading this post.

- A summary if these researches is in Amblard, F, Geller, A, Neumann, M, Srbljinovic, A and Wijermans, N (2010) Analyzing social conflict via computational social simulation: A review of approaches. In Martinás K, Matika D, and Srbljinovic A (Eds.) Complex Societal Dynamics – Security Challenges and Opportunities. Amsterdam: IOS Press. pp. 126-141. http://iros.morh.hr/_download/repository/Gelleretal1.pdf

- Epstein, J. M. (2002) Modeling civil violence: an agent-based computational approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, n. 99 Suppl 3, pp. 7243-7250.

- Here we use the NetLogo version presented in Wilensky, U. (2004). NetLogo Rebellion model. http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/models/Rebellion. Center for Connected Learning and Computer-Based Modeling, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL; Id. (1999). NetLogo. http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/. Center for Connected Learning and Computer-Based Modeling, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.

- Klemens, B., Joshua M. Epstein, J. M., Hammond, R. A. & M. A. Raifman (2010) Empirical Performance of a Decentralized Civil Violence Model, The Brookings Institution, Center on Social and Economic Dynamics Working Paper No. 56, http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2010/0625_empirical_performance_epstein.aspx.

- Michael Garlick and Maria Chli (2009) The effect of social influence and curfews on civil violence. Proceedings of The 8th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems – Volume 2, AAMAS ’09, Budapest, Hungary: International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, pp. 1335–1336, http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1558109.1558281.