By: Antonio A. Casilli (Centre Edgar-Morin, EHESS, Paris) [1]

By now you all must have a pretty clear opinion of James Cameron’s Avatar. Is it the new Star Wars? Or is it just another CGI-ridden crapbuster movie? You are entitled to your own opinion. As I am not a film critic, my job is not to change it. What this movie represents to me, and to many a colleague of mine, is a chance to resuscitate some forgotten pieces of cultural analysis written in the last 15 years – approximatively the time this movie has been in the making. As a concept, the avatar has a long history.

And a long history also means a lot of bibliographic references. And some of them still come handy to understand what the hell Cameron’s film is about. It’ like a garage sale, where I give away those old records I used to cherish a lot, so that some freshman neighbour with deejaying penchants can make a mashup mp3 out of them.

A few years ago, for example, the French journal Communications published an article of mine whose title, quite self-explanatorily, would read something like: Blue Avatars, about three strategies of cultural borrowing at the heart of computer culture.

Antonio A. Casilli (2005). Les avatars bleus, Autour de trois stratégies d’emprunt culturel au cœur de la cyberculture. Communications, 7 (1), 183-209

Yeah, well… maybe not that self-explanatorily, after all. Anyhow, in this article I gave form to a socio-visual genealogy of the avatar, as one of the main archetypes of contemporary culture.

Now I assume some of you don’t speak French. Also, some simply can’t be bothered to go through 30 pages of socio-babbling. So here I provide a summary of the main results of the article.

1) Define “avatar”. An avatar is a technologically-enhanced surrogate body that a user “wears” to perform physically challenging tasks. The Sanskrit word avatara, originally meant “embodiment of a god” and was mainly used to describe the human form Hindu god Vishnu used to assume to interact with mortal beings. In today’s popular culture it designates the presence of a human agent in a technologically-intensive environment. See for instance informational habitats: from popular applications like Messenger, to forgotten 3d communities such as Cybertown – the little bugger is all over the web.

2)Who came up with that? Apart from the Hindus, you mean? Well, French author Théophile Gautier published a novel by the same title in 1856. The main character, Octave, is a disabled young man that a mysterious doctor “who just came back from India” heals by swapping his body with a brand new one via an “electromagnetic equipment”. Admittedly, it sounds like James Cameron’s movie – Jake and his Na’vi alter ego through and through.

And I’m not accusing him or anyone of plagiarism. In the article I maintain the avatar is mainly a borrowed notion. “Cultural borrowing” is a social mechanism consisting in taking a style, a narrative or a visual canon originally developed in a certain context and transferring it into another one, thus attaining a fresh new meaning. Think Elvis appropriating rhythm’n’blues and turning it into rock’n’roll. The same goes on with avatars: science-fiction writers have borrowed them from religion; psychedelia have borrowed them from science-fiction; superhero comics have borrowed them from psychedelia. Internet culture have borrowed from superhero comics.

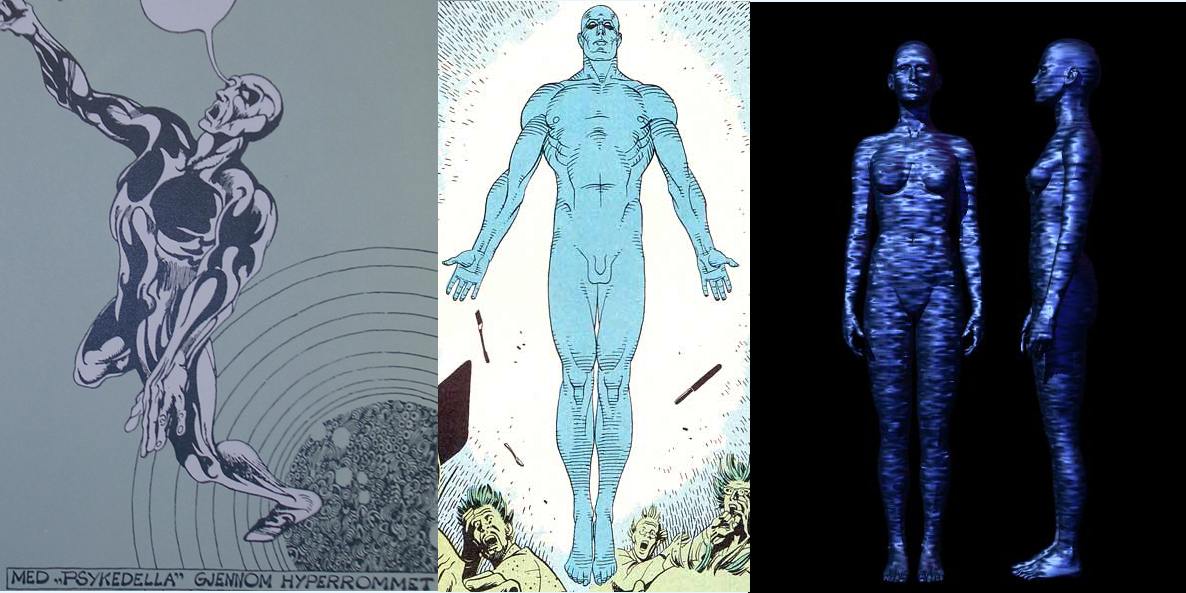

I could substantiate this lineage by dropping a number of authoritative references (I sure do it in the article). But sometimes an image is worth a thousand words. So here are three images equal, three thousand words I spare you.

The first one is “With psychedelia in hyperspace” (by Anon. in Rottenstein, Franz (1975) Het science fiction boek. Een geïllustreerde geschiedenis, Amsterdam: Landshoff, p. 131); the second is the infamous naked superman, Dr. Manhattan (by Dave Gibbons in Moore, Alan (1986) Watchmen, Chapter IV, New York: DC Comics, p. 10); the third one is a virtual character in an early online 3D community (by Tom Sepe in Vesna, Victoria (1998) Bodies INCorporated, http://www.bodiesinc.ucla.edu/).

3) So why is it blue? Yeah, that is a question Cameron gets a lot. How come the Na’vi are blue if they inhabit a “green planet”. Shouldn’t they be, like – green? Now, there is one explanation which points to the technological limitations that Cameron met when first he was developing the script. Back in the 1990s CGI-generated characters were difficult to render when it came to skins and hair. Thus the enormous amount of smooth, cerulean silhouettes in those years imagery. But, allegedly, Cameron’s movie took so long to be released precisely because he wanted to wait for the “technology to catch up with his vision”. Turns out his “vision” was borrowing too from the cultural and visual canon that had shaped all the avatars before him. The religious origin of the avatara sets the tone here. Middle- and far-Eastern religions are packed with blue-skinned gods: Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva (to say nothing of Krishna) in the Hindu tradition are all represented as blue men [for more details, see comment of Dec 29th, 2009 15 h 24 to this post], as well as the Shinto moon-god Tsuki-Yomi, the Egyptian goddess of the sky Nut, the Chinese god of justice Lei Kung, etc.

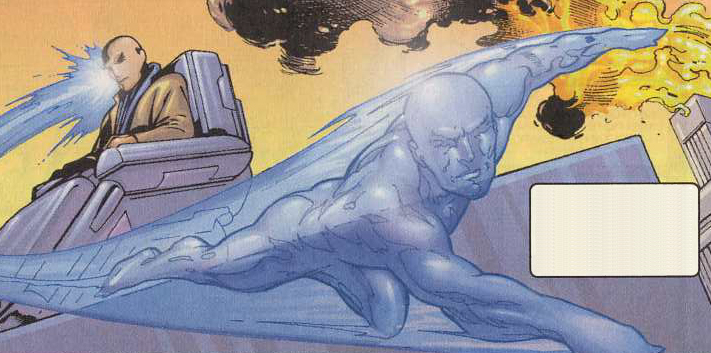

Of course popular iconography plays a major role too. Especially superhero, comics. Apart from the aforementioned Doc Manhattan, the trope of the blue body recurs in all kind of story involving superpowered beings. Again, one image instead of a thousand words – it’s a win-win!

4) What’s with the wheelchair? Jack Sully is a grunt wounded in battle, confined to a wheelchair. His physical disability highlights the gap between his actual body (his transient body, the “natural” organism that suffers from injuries and pain) and his idealized avatar (his sublime body, which is not subject to accidents and enjoys the pleasures of life in Pandora). Definitely, we put our finger on a major trope here. Other movies dealing with avatars have resorted to paralyzed characters in the past (see below).

Question: was it necessary to use a wheelchair to “highlight the gap” between a regular Joe and a cat-eyed giant blue alien? Weren’t they different enough? Again, it’s a matter of borrowing – again from the superhero lore.

Like Kantorowicz’s kings, superbeings have two bodies: a “secret identity” and a costume-wearing, public identity. While the latter displays all the signs of physical perfection, the former is burdened by some form of disability. Clark Kent’s signature glasses might have appeared as incapacitating enough back in 1938, when Superman first was published. Over time, physically-challenged alter egos have become a distinguishing feature of superheroes while not sporting their crime-fighting personas: Matt Murdok/Daredevil is blind, Don Blake/Thor limps – even Bruce Wayne/Batman is in a wheelchair after supervillain Bane breaks his back in the climatic issue #497 (1993). (Umberto Eco first developed this idea in (1978) Il Superuomo di Massa: Retorica e Ideologia nel Romanzo Popolare, Milano, Bompiani)

I think you got the point, no need for me to go on an on. Anyway, if you were interested in me ranting, you would have read the article already. 😉