by Antonio A. Casilli (Centre Edgar-Morin, EHESS) [1]

By now, you might have heard of Chatroulette, if you are hip and tech-savvy if those two things at the sides of your face are your ears. By the way, I hope you did not click on the link. It’s not safe for work. And by that I mean you will be sucked into a world of sheer immorality which will challenge all your values and potentially wreck civilisation. Or (but this is simply my own guess) it will lead you to yet another overhyped internet chat service designed to put you in touch via webcam with random strangers.

A few facts

So, bottom line, Chatroulette goes something like: you log in, you bump into someone, you evaluate, you click on “next”. Basically, each time you connect you have to ask yourself “Do I like this person?”. If you do, just go on chatting. If you don’t, just “next” him/her and the service puts you in contact with someone else, anybody else. It might be a teenage boy making faces, or a beautiful girl with a generous cleavage, or an old pervert doing whatever it is that perverts do on-screen.

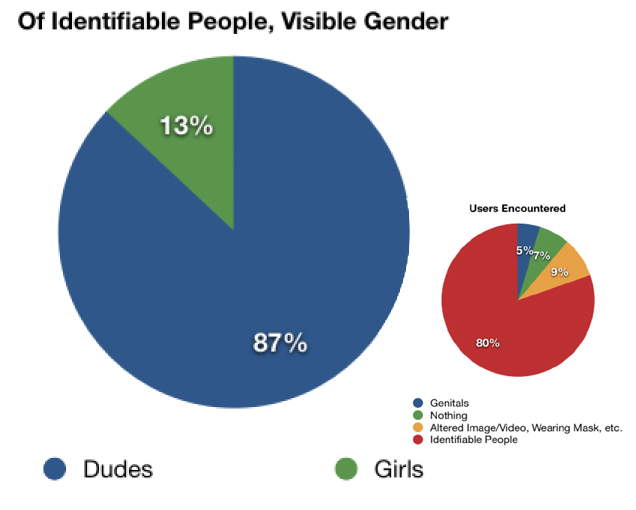

There are actually fewer chances you bump into the second (or the third) case than the first. This will come as a surprise to the journalists and panic-mongers of all sorts, but an initial survey gives us a male/female users ratio of almost 9:1 and scales down the inappropriate content to a tiny 5% of the overall sessions.

Hopefully, soon we’ll have more accurate data as to other important variables, like geographical location, socio-economic status, education. But let me tell you that, as necessary as it may be, this kind of descriptive analysis tells us little about the social process at stake here.

“Nexting”, or should we say “mating”?

What is intriguing about Chatroulette is its interface, relying on the signature feature of “nexting”: by clicking on the “next” button, users browse through hundreds of potential partners until they settle down with someone. Now, satirists have compared that to cruising (intended as looking for sexual partners in public places), another well known contemporary social behaviour.

But, sociologically speaking, “nexting” is nothing more than a mating mechanism. How do we choose our mate? Whether it is our spouse, or a travelling companion, or a chat partner, for quite some time now this has been a bit of a riddle for social scientists. Traditional approaches provided answers in terms of maximising utility. According to these, we “shop” for mates, implying we should be able to gather them all together, and then choose one among them, after weighing our options according to objective features – like we do at a supermarket. If you have been following this blog, you might have noticed that I am slightly skeptical towards these theories. It’s not that I dismiss these approaches as unrealistic. I only maintain that they apply to specific social settings, like, I dunno, if you are a sultan and you have to choose a bride from a pool of candidates.

As titillating for the male ego as this situation might be, I’m convinced that in our societies mating (and Chatroulette, for that matter) works according to a “serial” logic. We mate/chat with someone, then we evaluate, then we choose another, then we evaluate – and so on. This is known as the “next best mate rule”, as described by Peter Todd more than ten years before Chatroulette.

Todd, P. M. (1997). “Searching for the next best mate”. In R. Conte, R. Hegselmann, and P. Terna (Eds.) Simulating social phenomena, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, pp. 419-436

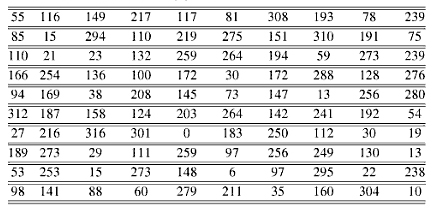

According to Todd, mating does not equate to a rational choice of an optimal partner. Individuals use “fast and frugal” heuristics to find a semi-ideal mate after a certain number of tries. So from this point of view, mating is not really about choosing someone: it’s more about choosing when to stop. Just imagine, for the sake of simplicity, that you date one person at the time and that each person has a certain score in terms of compatibility with you. If we put together all the potential mates you have, we’ll have a table like this:

To get the idea of how people work in Chatroulette (or in romantic life, Todd insists) just cover the boxes of this table with your hand and start revealing them one by one. The first has a score of 55. Do you stop? Do you “next”? Of course it depends on the way you value that score. Let’s say that, after a few tries, you figure out a certain standard. That’ll help you make your choice. Not a rationally-informed one though: maybe you just choose someone good enough according to the average of your previous mates, or according on the best score of your previous mates. Or according on just how tired you are of looking…

Disposable social ties and the end of community as we know it

Of course this is a very simplistic take on a very complex social behaviour, but it helps us formulate a pretty compelling hypothesis: people do not “next” interminably. Eventually they stop. In Chatroulette this means that they’ll find someone special enough to deserve their attention and time. Someone they would like to establish some kind of online link to. If they were on Faceboook they would become friends, on Twitter they would follow this person. But on Chatroulette you have no such options. Once you’ve found that special someone, there’s no way to search, bookmark, or reconnect with him/her.

Social networking services have often been criticized for creating weak ties – as opposed to real, strong ties connecting individuals with their families, neighbours and peers offline. Chatroulette pushes the envelope by creating disposable social ties, thrown away after one use. According to the people at the Web Ecology Project this operating principle describes a “probabilistic online community”, a social group where common practices, distinctive behaviours and a definite cultural identity emerge as a result of a stochastic process.

Yeah, Chatroulette is the Twilight Zone version of Myspace. Like in Myspace, you have an online community populated by distressed juveniles fuelled by a fast-paced urge for outrageous self-display. Plus, like in that old Twilight Zone episode, you have a morally shady service that provides random strangers with a big button allowing them to make other random strangers disappear.

More to the point, the very notion of “probabilistic community” sounds uttely paradoxical to sociologically-trained ears. Since its 19th century beginnings, sociology has been concerned about the difference between the close-knit mutual bond connecting human beings in a “community” (Gemeinschaft) and the anonymous, alienating face-to-face relations that are common in what was described derogatorily as “society” (Gesellschaft). From Tönnies (Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, 1887) to Putnam (Bowling alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, 2000), the grand sociological tradition has constantly stressed the sharp opposition between the sense of belonging, the togetherness of a community and the shallowness of “totally socialized society” (Vergesellschaftete Gesellschaft, as defined by Th. W. Adorno Thesen über Bedürfnis, 1972).

Chatroulette seems to question these distinctions, as it brings together disparate individuals with no strong ties, who end up sharing a common culture and peculiar codes of conduct. Before we discard the idea of Chatroulette being a community, let’s just wait and see how the service develops. Maybe, if it survives its initial fad status, we’ll see the appearance of a full-blown SOVC (in psychological parlance, a “Sense Of Virtual Community”). After all, this has been the case for many other online forums of the last 30 years, from CommuniTree to 4chan. Maybe, this will also help us update our notions and categories. After all, sociology is almost two centuries old. Auguste Comte didn’t have an Internet connection. He never had to deal with webcam-based social interactions. If he did, I’m pretty sure he would have enjoyed it…